Birmingham’s autobiography, Pleasant Places (1934), relates an episode which shows his deep faith in Christianity. While Birmingham was the rector of Westport, there were four churches in the suburbs besides Holy Trinity Church near the center of the town. Every Sunday Birmingham and the curate took turns to give services at those churches. When one gave a service at the church in the town center, the other went out to give services at the four churches in the suburbs. It was a journey of more than twenty miles to go around those four churches. At the beginning Birmingham went on horseback, and later by bicycle.

One of those churches was located in the south-east of the town and the congregation was at most fifteen or sixteen. They were very faithful people, though. Inside the church two fireplaces were set five feet high from the ground. Each member of the congregation brought turf from their houses and burnt it in the fireplaces to warm themselves. But, as the smoke did not go through the chimneys smoothly when the wind was strong, the room got so thick with the smoke that Birmingham and the congregation could not see each other. Yet they came every Sunday to attend the services.

Holy Trinity Church near the center of Westport.

Holy Trinity Church near the center of Westport. The ruin of the church in the south-east of the town.

The ruin of the church in the south-east of the town.Due to the success of the productions of General John Regan in London and New York in 1913, Birmingham made up his mind to leave Westport to give lecture tours in America. World War I broke out in 1915 and Birmingham joined the British army in France as a chaplain from 1916 to 1917. Ireland experienced a great turmoil around this time. Their fight for independence from Britain became fiercer. The Easter Rising broke out in April, 1916, in which the Irish rebels waged a bloody war against the British troops. The Irish Nationalists, considering that “England’s extremity was Ireland’s opportunity”, hoped for a German victory in World War Ⅰ. Although Birmingham supported the Nationalist cause, he believed that this Nationalist sympathy with Germany was wrong and that England was right, and volunteered for a chaplain for the British army.

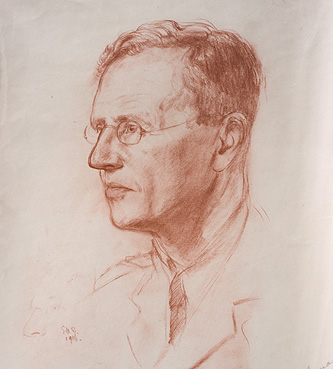

Birmingham in 1916

Birmingham in 1916Birmingham had four children; a son Robert, then a daughter Theodosia, next a second daughter Althea, and finally a second son Seamus. Robert, who became a reporter for The Irish Times, fought against Germany in the front line of the British army and got wounded. Althea also accompanied the British army and worked to serve food for the soldiers. It is probable that his war experience and the turmoil of Ireland deepened Birmingham’s conflict regarding Nationalism and Unionism, made him a “maverick”, and served to develop his sense of humor at the same time.

Birmingham’s conflict regarding Nationalism and Unionism at that time is noticed through the two letters he wrote to his acquaintances. On May 18, 1918, Birmingham wrote a letter of caution to Sir Edward O’Farrell who arrested the leading Sinn Feiners on suspicion of intriguing with Germany. In the letter Birmingham advised him to release them unless he could prove that they were guilty because the Irish people would raise a more greater rebellion than the Easter Rising. On the other hand, Birmingham wrote a letter to Lord Mounteagle on St. Patrick’s Day in 1920 and said, “I think that Dominion Home Rule is probably the most desirable constitution for Ireland; but I think that the present time is singularly unsuitable for trying any constitutional experiments. We, like the inhabitants of every other country in Europe, are passing through a torrent of crime, such crime as seems invariably to follow a great war. Until we are through it constitutional changes seem to me singularly unwise.”

For four years from 1918 to 1922, Birmingham served as the rector of Carnalway, Co. Kildare. The Nationalists’ hatred against Britain was at its peak after they witnessed the brutality of the British army during the Easter Rising, and the terrorist campaigns by Sinn Feiners were increasing day after day. As Birmingham also suffered a number of terrorist threats in Carnalway, he resolved to depart from Ireland.

Looking back on his involvement with the Nationalist movement, Birmingham said in Pleasant Places, “With this story I must end these notes of my brief and unfortunate connection with Irish politics. It is not for me to write a history of that period of high hopes, shining enthusiasm and ghastly deeds. For me it is enough to have learned that greater than all these things is love.” (p.194)

While Birmingham was the rector of Carnalway, his eldest daughter Theodosia married a Catholic from Britain about 1920. Although she remained to be a Protestant, their children were brought up as Catholics.

Theodosia and her two children

Theodosia and her two childrenAccording to Hilda O’Donnell, Birmingham might have been hurt by this marriage, but “in his usual kindly, generous fashion” he accepted the other person’s point of view and remained on friendly terms with his daughter and her husband. O’Donnell also points out that the marriage is the chief reason why there are not any traces of criticism of Catholics in Birmingham’s later novels. (Hilda O’Donnell, “A Literary Survey of the Novels of Canon James Owen Hannay,” 1959, pp.121-122)

After leaving Ireland, Birmingham served as the rector of the British Legation in Budapest, the capital of Hungary, for two years from 1922. Then, in 1924, he became the rector of Mells, Somersetshire, in the south-west of England. Mells is a small hillside village with a population of six hundreds and, in St. Andrews Church where Birmingham gave services, there is a memorial bust of him with the inscription, “James Owen Hannay (George Birmingham), MA. Litt. D. Dublin, Canon of St. Patricks, Rector Here, 1924-1934”.

On Sunday, January 28, 1934, Birmingham gave a sermon about Isaiah, a prophet appearing in The Old Testament. When Jerusalem faced the crisis of Assyria’s invasion, Isaiah said to the people, “Be quiet. Fear not. Your strength is to sit still……Let Him be your fear and you need fear no other. Let Him be your dread and you need have no other dread.” Birmingham’s sermon, in which he admired Isaiah for his unfailing faith in God, was aired throughout Britain by radio. Many listeners were so much moved by his sermon that they wrote letters of gratitude to him. About sixty of those letters are reserved in the Papers of JO. Hannay in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library of Trinity College Dublin. (http://www.tcd.ie/Library/manuscripts/index.php) They expressed such words of gratitude as “It was such a comfort and help to me…I am recuperating from a nervous breakdown…I have had a terrible time, but in my Gethsemane, I have learned more and more of God. May I ask for your prayers for a full and complete recovery.” “This is a somewhat belated ‘Thank you’ from 2 lonely sisters who received help from your broadcast address…Remember us ― if convenient ― in your prayers.” “I was most delighted to hear your Broadcast Service this evening from the Church of my early childhood days…I shall be looking forward to your next Broadcast Service…”

Birmingham with his family members

Birmingham with his family members On the left is St. Andrews Church.

On the left is St. Andrews Church.From 1934 to 1950 when he died, he was the Canon of Holy Trinity Church in South Kensington, London, (http://www.htsk.co.uk) where he underwent the German air raids during World War Ⅱ. Through such hardships as his involvement with Irish politics, World War Ⅰ, his daughter Theodosia’s marriage with a Catholic, and World War Ⅱ, Birmingham might have come to hope more earnestly for reconciliation between every human being, every creed and every principle because he was a devout and faithful Christian. He might also have convinced himself of the idea: “Sticking to one’s own principle and getting angry about other people is a very stupid thing. Every human business ought never to be taken seriously. It is always comic and should be treated as a joke.” That is to say, Birmingham might have fostered the belief that humor is indispensable for reconciliation between every human being.

Over the Border (1942) is another humorous novel that represents Birmingham’s sincere wish for reconciliation between every human being.

This novel was written in the midst of World War Ⅱ, and its settings range over Hungary, Ireland, Northern Ireland and Britain. In a Co. Donegal town on the border of the South and the North, Lord Malmore, a landlord of British descent, lives with his family in a mansion which his antecedents have succeeded to for generations. His only daughter Una, while traveling in Budapest with her friends, meets a young German diplomat, von Rotenstein, and falls in love with him.

Lord Malmore can not bear it that his daughter falls in love with a man from an enemy country. Una’s aunt, Lady Margaret, is a widow and breeds racehorses in Co. Donegal. She is sent over to Hungary on the mission of parting Una from the German. However she is treated with great courtesy by the German and returns home without fulfilling her mission. Una stays in Hungary and marries him.

Afterwards von Rotenstein is appointed to a post in the German Legation in Dublin, for Ireland is a neutral country. He comes back with Una, and visits her family in the border town. Soon after, Belfast undergoes a large-scale German air raid, in which many citizens are killed. Lady Margaret convinces herself and her friends that von Rotenstein has collected information about Belfast while staying with Una's family, sent the information to the German Air Force through the German Legation in Dublin, and made the air raid possible. She expresses her concern saying that, if they leave von Rotenstein intact, Londonderry will be air-raided next time. She insists that they must capture the German and hand him over to the British military authority.

It is Jimmy MacNiece that agrees with Lady Margaret at once. He was born in Belfast and graduated from Oxford University. He got acquainted with her in Hungary, enlisted in the British Air Force, got wounded in the war, and is now at home for convalescence. He makes up a plot to kidnap von Rotenstein in conspiracy with Lady Margaret and their friends while the German stays in Una’s house, taking him by car to Northern Ireland and handing him over to the British military authority.

MacNiece and his company raid Una’s house at midnight, but an unexpected thing takes place. Von Rotenstein says to them, “I will tell you who you are. You are agents of the Gestapo. For some time I have known that you were watching me. Now you have me at your mercy. Shoot.” (p.176) When MacNiece and his company are at a loss, Lord Malmore invites them into the dining room and has a banquet with them. Von Rotenstein tells them the true reason why he has come to Ireland. Then Una asks Lady Margaret to put her husband under her protection.

In return for Lady Margaret’s help, the German speculates on the co-ownership of her racehorse, Hesperides. The horse wins a big race in Britain, and British newspapers give sensational reports of it: “Our readers can scarcely have forgotten the sensational escape of the Bavarian Count von Rotenstein from his native land…his trip to this country was pre-arranged…The reason for this smoothing of the way for a Nazi diplomat anxious to visit this country is now clear…Von Rotenstein was the owner of Hesperides.” “Hesperides was entered for the race and actually ran under the name of the Irish lady of title…but the unfortunate fact is that she has connextions by marriage with people highly placed among the Nazis. Ought not the Stewards of the Jockey Club to have made some inquiries about the curious ownership of this horse before it was allowed to run and win?” “The owner, the real owner of Hesperides, was naturally anxious to see his horse win…Acting with strict propriety he asked permission to visit this country in order to see the race. Nothing could be more correct. Nor do we blame those who granted the permission. We are, after all, a nation of sportsmen. Our hearts go out-the great heart of the inarticulate British public goes out to any one who owns a racehorse, whether he is friend or foe. The granting of permission to von Rotenstein to visit Newmarket yesterday is strictly in accordance with our best national tradition” (p.201)

Lady Margaret, Jimmy, Una and other people who know the truth are so busy spending the prize money they have won from the race that they do not make any complaints about those newspaper companies.

This novel was written in the midst of World war Ⅱ when Britain was fighting a fierce battle against Germany. However, as this novel is filled with humor, it gives the impression that Birmingham did not hold any detestation of Germany. The title of this novel, Over the Border, initially comes from the fact that the characters come and go to Hungary, Ireland, Northern Ireland and Britain over their borders. At the same time the title seems to imply that they cross the border of every creed and principle and come to reconciliation.

Although Birmingham’s humorous novels look absurd and nonsensical on the surface, they have deep implications in actuality. As a critic rightly points out, they represent “the philosophy of the absurd”. They reveal the universal truth; that there are comical aspects in every human behavior and they ought never to be taken seriously, and that the spirit of humor is indispensable for reconciliation between every human being.

| << BACK | NEXT >> |